Key Signatures

What is a key signature?

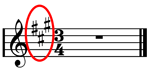

The most straightforward definition is that it's the group of sharps or flats just after the clef on every line in a piece.

More accurately, you should regard the signature and the clef together as defining the pitch of the notes on the stave and defining which of the 7 notes that we use are sharp (or flat) notes.

Some facts

- A key signature can have up to 7 flats or up to 7 sharps

- A key signature will never contain both sharps and flats

- There is only one signature that has 'n' sharps - there's a table below.

- Each signature has the effect of pushing one or more notes up or down a semitone, moving them closer to one neighbouring note, and further from the other. For example F# is closer to G than F is, but it's further from E.

Why do we need a key signature?

If we play a scale of C, going through all the letters of the alphabet, we produce a "major scale of C"; the jump in frets between notes is 2,2,1,2,2,2 and finally 1. You can even play the scale starting on fret 3 of string 5 and going up the string, rather than across the fingerboard. You'll play frets 3,5,7,8,10,12,14,15. It's cumbersome, but this is about understanding, not performing.

If you try the same scale starting on the G that is on fret 3 of string 6, going up via the same frets, you'll discover that the penultimate note you play is not F, but rather it is F#. We have just seen that the key of G requires one sharp and it's F.

You can start on any fret and any string and play any major scale, simply by going up the string 2,2,1,2,2,2,1 frets and discovering the notes you've landed on. When there is ambiguity (the note is G# or Ab, for example), pick the choice that gives you one of each letter name.

Minor scales

Ever wondered why the key signature with no sharps is C, and not the first letter of the alphabet? Read on

Once the music theoreticians got their hands on the minor scales, things became mucky, but to understand key signatures, we define the "natural minor scale" as the scale that you get when you play all the letter names starting on A with no key signature (which gives us a sequence that goes up 2,1,2,2,1,2,2). The natural minor scale has a modal, folk-like character redolent of traditional western music. "A" is therefore a relevant base from which to begin, and the minor scale is the natural (pardon the pun) starting point.

If we take a different starting note but follow the same "recipe", we generate a natural minor scale in any key. As we go ascend, we discover which notes are sharp or flat, and therefore what key signature we need for that starting note. We find the grouping of sharps or flats looks familiar - the fifteen different key signatures have the same collection of sharps or flats as in the major keys and we can summarise it all in a little table.

A table of key signatures

| Signature | Which notes? | Major Key | Minor Key |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7b | B E A D G C F | Cb | Abm |

| 6b | B E A D G C | Gb | Ebm |

| 5b | B E A D G | Db | Bbm |

| 4b | B E A D | Ab | Fm |

| 3b | B E A | Eb | Cm |

| 2b | B E | Bb | Gm |

| 1b | B | F | Dm |

| none | - | C | Am |

| 1# | F | G | Em |

| 2# | F C | D | Bm |

| 3# | F C G | A | F#m |

| 4# | F C G D | E | C#m |

| 5# | F C G D A | B | G#m |

| 6# | F C G D A E | F# | D#m |

| 7# | F C G D A E B | C# | A#m |

The patterns are not easy to find at first, but look at the order notes go sharp - the opposite order to which they go flat. And the list of keys going down the page has the same sequence of letters as the removal of the flats and the addition of the sharps. Each pattern contains the letters of the alphabet in two interlocking ribbons - every second letter is in alphabetical order.

A mnemonic

We add sharps in this order... Father Christmas Gave Dad An Electric Blanket

And flats go in this order... Blanket Exploded And Dad Got Cold Feet

But what about Major and Minor?

Every Key Signature defines exactly one major key and one minor key. Unsure whether it's major or minor? Happy pieces are Major.

Still unsure? Have a look at the last bass note - it's 99% sure to

be the key of the piece.

Hang on 12 doesn't equal 15!

We have 15 Key Signatures (7 flats down to none, up to 7 sharps), but there are only 12 semitones in an octave. What is happening?

That's because C# and A#m at the bottom of the table are the same notes as Db and Bbm at the top - the top 3 entries and the bottom three entries are duplicates of each other.

There's too much to learn!

As guitarists, we seldom play in more than one flat, or more than 4 sharps. The table we really need to be at ease with is a lot smaller...

| Signature | Which notes? | Major Key | Minor Key |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | B | F | Dm |

| none | - | C | Am |

| 1# | F | G | Em |

| 2# | F C | D | Bm |

| 3# | F C G | A | F#m |

| 4# | F C G D | E | C#m |

In fact, as music readers, as opposed to music writers, we don't actually have to learn anything - every time we see a piece of music it will fit the same pattern, and we soon learn the pattern by repetition - the written music actually reinforces the rule, rather than requiring us to know the rule.

See also

The time signatures article

Download this teach-in

Download an e-book of all the teach-ins

Back to the FAQs contents